From a ripple to a wave of connection

Posted by The Cares Family on 25th August 2022

Please note: this post is 42 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

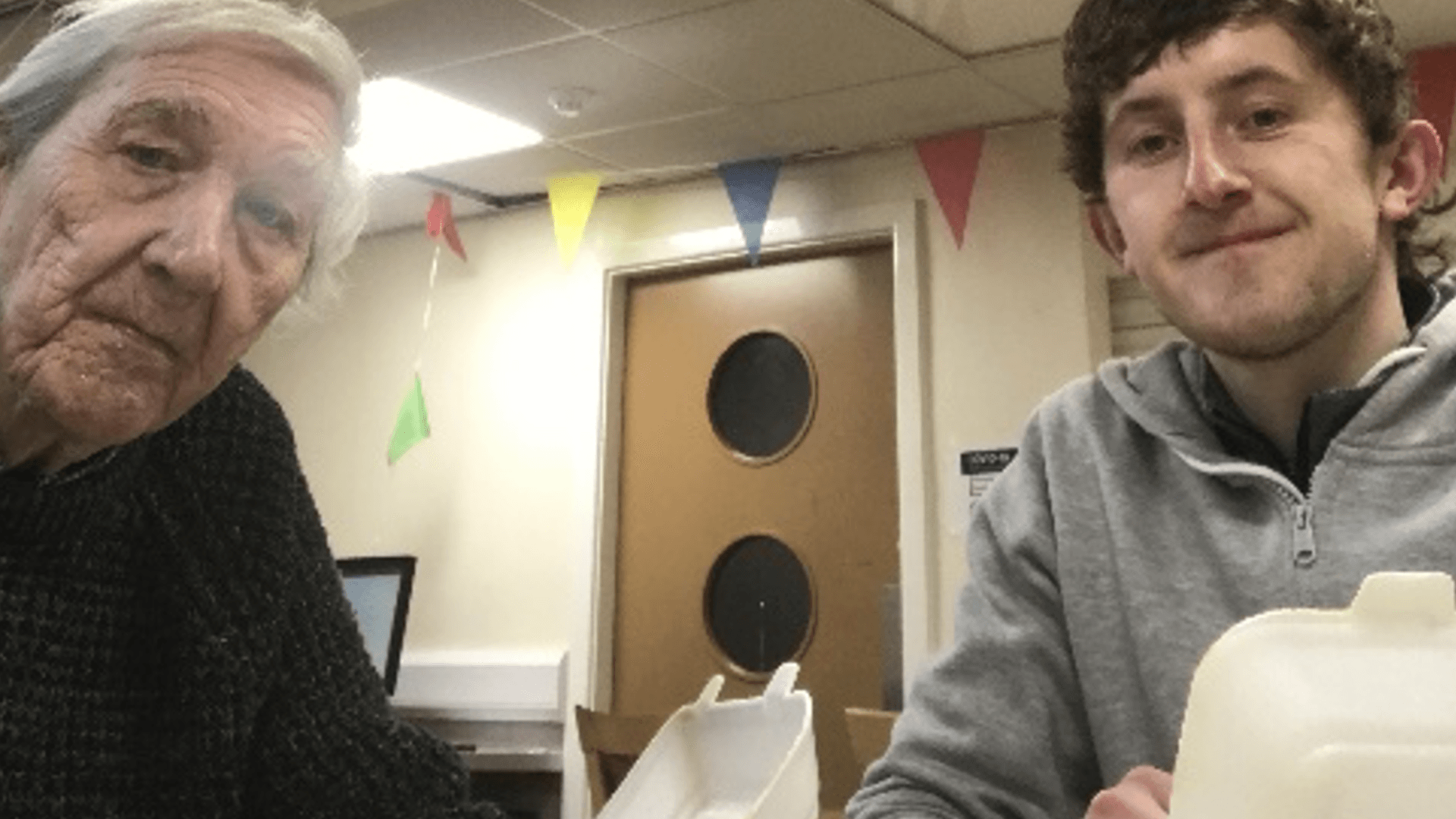

If you’re not familiar with The Cares Family, we’re a network of charities which work to bring people from different generations and backgrounds – and with different experiences of life – together to build community and connection. Since the first of our branch charities, North London Cares, was established in 2010, our network of charities has brought together over 26,000 older and younger people – we refer to them as older and younger neighbours – to meet, mix, form connections and experience the stuff of community.

We’re proud of what we’ve achieved over the course of the last eleven years, but we also know that we’re but one organisation among many engaged in the vital work of building more socially connected communities, which is why it’s such a pleasure to be here today.

I want to speak to you today about why we at The Cares Family believe that many of the community organisations represented here at Only Connect might be described as twenty-first century connecting institutions. And I also want to explain why we believe that the work of organisations such as ours in enabling people to feel less lonely, more united and that they belong is only going to grow in social and political importance in the years to come.

Our loneliness epidemic

Some of you will know that our network of charities has focused for the most part during its first eleven years of existence on addressing and alleviating the devastating loneliness which is wrecking lives in communities across our country.

Everyone here will be familiar with the facts and figures. 9 million adults in the UK say they often feel lonely. Two in five people over the age of 65 — two in five — say the TV is their main form of company. 17% of older people haven’t spoken to a friend or relative in a week and 11% haven’t shared a meaningful interaction with another human being in a month. And it was estimated in the years immediately preceding the pandemic that one in ten patients presenting to a GP was an older person suffering from no medical condition other than feeling lonely.

But loneliness is not just a late-in-life problem. Quite the contrary. Multiple studies have shown that young people between the ages of 16 and 24 are at least the second loneliest age group in our society and may actually be the loneliest. Indeed, polling conducted for Cares last year revealed that, while three quarters of UK adults say they experienced feelings of loneliness during the pandemic, nine in 10 18-to-34-year-olds say the same. Meanwhile, one in five young mums say they feel lonely, I quote, ‘always’.

A recent report by the economist Sir Angus Deaton for the Institute for Fiscal Studies concluded that the proportion of middle-aged Britons dying ‘deaths of despair’ – early deaths related to drug and alcohol abuse or suicide – doubled between 1993 and 2017. And suicide is in fact now the single biggest killer of men under the age of 45 in this country. Little wonder, then, that the Royal College of GPs has declared loneliness to be a public health epidemic, following a similar pronouncement by the US Surgeon General Vivek Murthy.

Even without driving a person to take their own life, loneliness can kill. In its chronic form, it has been shown to harden our arteries, to increase inflammation of the gut, heart and joints and to slow the production of antibodies. It brings on strokes, dementia, anxiety and depression. Ultimately, while obesity increases our chances of premature death by up to 20%, and dependency on alcohol does so by 30%, experiencing a pronounced absence of meaningful relationships in our everyday lives increases our chances of dying early by a sobering 45%.

So, we at The Cares Family have, throughout the last eleven years, been primarily focused on doing what we can to tackle this momentous and urgent challenge. We set out to bring together older and younger neighbours to share positive and meaningful experiences exactly because these were and are the two age groups in our society who are most likely to suffer from loneliness.

Our model wasn’t, to be clear, devised to meet the needs of those who suffer from extreme forms of debilitating chronic loneliness. Those cases, sadly, are often fuelled by or lead to addiction and mental health issues which we simply aren’t set up to address. But our programmes do provide purpose-built spaces in which people who may not meet that threshold but who are nonetheless suffering from a deeply pernicious form of loneliness – or who might be teetering on the edge of isolation – can forge new relationships and associations.

To my mind, our work is aimed at weaving a safety net of social connections which is strong enough to prevent older and younger neighbours from slipping through the gap into the habits of isolation and estrangement which shape far too many lives in our age of atomisation. It is about channelling and unleashing the preventative potential of associational life. Indeed, as we have sought to continuously improve the design and delivery of our programmes and to expand into new communities, we at Cares have become increasingly conscious of the ways in which our work might be said to respond to and defuse drivers of disconnection beyond loneliness and isolation.

Growing division, rising dislocation

We quickly became aware that one of the key benefits which younger neighbours derived from taking part in social clubs or in our Love Your Neighbour programme was the opportunity to meet and mix with older people with deep ties to their local area.

Oftentimes, those younger neighbours were rich in connections but poor in roots, having moved to a new city far from where they grew up. Hearing older neighbours, many of whom were rich in roots but poor in connections, recall what their local area was like in the past helped them to feel that they knew, understood and so belonged within their neighbourhood and community. In turn, coming to understand what the younger people around them do for a living and in their social lives – what goes on in the office blocks and bars which they can otherwise feel are closed off to them – enables older neighbours to feel more connected to the fast-changing places around them.

In this way, our programmes work to address the rising dislocation – the loss of belonging – which research by the think tank Onward suggests impacts on our quality of life ‘in critical ways’, and which cuts us off from the communities around us.

In addition, as we at Cares have grappled with the reality of social disconnection, we’ve come to appreciate the degree to which an inability to invest trust in and empathise with people who we perceive to be different from ourselves is fracturing our society. We know that, when people from different walks of life connect in positive and meaningful ways, trust grows. But research by the Social Integration Commission has demonstrated pretty definitively that – even where we do live in socially mixed areas – we aren’t actually mixing with one another very much.

In modern Britain, roughly half of people with university degrees have exactly zero friends without degrees. Similarly, half of UK adults say they only have friends who belong to their own ethnic group. And almost half of non-Muslim Brits say they have never had any close contact with a Muslim at any point in their life.

And ours is not universally a country in which people from different social and cultural backgrounds and with different experiences of life do live side-by-side. The social geographer Danny Dorling has shown that, in every decade between 1970 and 2000, those who earned more and who were more educated moved further and further away from those who earned less and were less educated. Today, Black and Asian Britons and members of non-British white communities are increasingly spreading out and living side-by-side in the same places, but white Britons are increasingly leaving the newly diverse areas where this is occurring. In fact, and I find this statistic amazing, black and white Britons are now more spatially segregated than white and Latino Americans.

These patterns of separation and segregation are reflected too in the institutions which shape our lives. A study which I helped to produce for The Challenge in 2017 concluded that 41% of secondary schools in the UK are so unrepresentative of their local community that they are in effect entrenching or at least contributing to ethnic segregation in their area.

In light of these facts, it’s perhaps unsurprising that 50% of us believe that this is the most divided Britain has ever been. Or that we increasingly seem to find ourselves waking up to election results – and yes, referendum results – and wondering who the heck the people who voted for the other side were, because we sure as hell haven’t met them.

Social segregation is, much like loneliness, decidedly bad for our health. When we are confronted with people with whom we don’t feel we share a natural affinity, our stress levels rise. Lower levels of intergroup trust consequently result in higher rates of cardiovascular disease and of mental health issues – especially, in the latter case, among children.

Beyond health and wellbeing, social segregation undermines trust in democratic norms and renders us vulnerable to the siren songs of tribal populists and authoritarians.

And a lack of intergroup contact has been shown too to limit economic growth, including through creating barriers to trust-based co-operation between businesses; through constraining the flow of both investment and money-generating ideas across society; through generating productivity costs associated with reduced wellbeing; and through stifling social mobility in a variety of ways.

A systemic and cultural challenge

Last year, in his Community Power lecture for the Local Trust, the former Chief Economist of the Bank of England and current CEO of the Royal Society of the Arts Andy Haldane summed the situation up well when he argued that the UK is experiencing ‘a crisis in social capital’ – in ‘trust and engagement, relationships and reciprocity, communities and civic institutions’.

At Cares, we’ve come to redefine the problem which we’re seeking to address as a serious and mounting crisis of social disconnection which can be detected in rising rates of isolation and loneliness, dislocation and division.

This evolution in our analysis is reflected in our leadership development programme, The Multiplier, which is run by The Cares Family nationally rather than by our branch charities. The Multiplier is aimed at supporting community leaders to deepen the impact of initiatives which work to bridge an array of social and cultural divides and to build belonging in ways which matter to their community.

In any case, the label which we choose to apply to the crisis we're facing isn’t especially important. As I insist on saying, social capital, social connection; tomato, tomatoe – the thing that matters is finding a way to call the whole thing off. And there are, quite simply, no easy answers in that respect – because there can be no doubt that this crisis is both cultural and systemic.

Researchers inspired by Robert Putnam’s seminal study of social capital in the USA, Bowing Alone, have pinpointed the decline of community associations, from trade unions to faith groups and broad-based voluntary organisations, as a trend which has led people on this side of the Atlantic too to withdraw from one another. The sociologist Eric Klinenberg has charted the deterioration of the social infrastructure – the pubs, libraries and assorted bumping places – which once provided space for community and connection. And, in 2019, the former Chief Economist of the IMF Raghu Rajan published The Third Pillar – a fascinating and authoritative account of the way in which our societies and economies have fractured and floundered because our political debate places excess emphasis on the role of both the market and state, while largely overlooking the third pillar of community.

Perhaps as a result of these systemic trends, we’ve become a country which is at once thirsty for connection and fundamentally passive in its approach to building community. This slightly maddening truth is perhaps best expressed in a recent survey finding from the Be More Us campaign: 72% of people in the UK say that knowing your neighbours is important, but 73% confess that they don’t know their neighbours themselves. So, how should we seek to overcome our crisis of disconnection even while acknowledging that it’s both structural and engrained?

Achieving systems-level change

At Cares, we are increasingly seeking to develop systems-level responses to systems-level challenges. To spur a national ripple effect of connection by openly sharing our learning with others; by influencing policy and decision-making; and by seeking to shift narratives, attitudes and behaviours. This approach has found expression in our hopes of expanding The Multiplier to support more community leaders to bridge divides within their communities and build belonging in their own ways.

And it has also led to our developing plans to give away our intellectual property. We believe that communities in many places in which we don’t currently work would benefit from the provision of social clubs modelled on The Cares Family’s approach or of a Love Your Neighbour-style intergenerational matching programme. But we also believe that those programmes will wind up being more impactful if they are built and managed by people who really knew and understood those places.

We have long held to the view that the nuances of how to build community in a village in Cornwall will almost certainly be understood best by the people who call that village home. And that the most effective approaches to dismantling disconnection in a town in Nottinghamshire will reflect a deep knowledge and love of that town which we can’t claim to possess. Perhaps Glasgow could benefit from the effective establishment of something like a Glasgow Cares, and Bristol something akin to a Bristol Cares, but we don’t see why the resulting programmes need to be delivered by us – or to have the Cares tag applied to them.

That’s why we’re in the midst of developing a programme aimed at supporting local authorities, charities and community organisations to adopt and adapt our model in a way which will work for their place, which we hope to be able to roll out in 2023.

And, finally, our focus on bringing about systemic change also underpins our work in advocating for a drive to build what we describe as twenty-first century connecting institutions.

Unleashing a new boom in our associational life

We recently launched a podcast in partnership with Onward, which is entitled Building Belonging. The podcast is available on Apple, Spotify and all good podcast providers. It seeks to explore the stories behind what our two organisations would contend are a new wave of community and civic initiatives which have sprung up within communities across the UK in recent decades in response to a felt need for belonging.

These connecting institutions work in purposeful ways to inspire cross-community feelings of empathy, trust and togetherness. To support people to forge strong, thick or deep ties, including across social, cultural and generational lines, and to experience a sense of shared purpose and identity.

So what marks out a connecting institution?

An initiative of this sort brings people from different backgrounds and generations together not just to share space or passing encounters, but meaningful experiences. These experiences may be in some way intense and thus memorable; they might be co-operative but challenging and so inspire a sense of shared endeavour; or they may encourage people to reveal something of themselves, in turn engendering feelings of intimacy.

Connecting institutions empower people equally. Their work is rooted in the reality that we all have something to give to one another, and the relationships which they seek to foster are mutually beneficial and – as far as is possible – reciprocal.

And, crucially, connecting institutions are designed not just to make life more liveable, but to make life worth living. Creating space for meaningful and authentic engagement is at the very core of their work.

To coin a phrase, they are spaces in which we need only connect with one another.

A café is a space in which people rub along together, but it takes the application of the Chatty Cafe model for it become a space in which people are actively brought together to connect with one another positively and meaningfully. To provide another example, a park is shared community space; a Parkrun is a connecting institution. And, as I’ve already alluded to, it’s my hope that a number of you will recognise your own organisations and initiatives in the criteria which I’ve set out today.

Now, you might question whether trying to invent a category of social institution is a remotely useful thing to try and do. It’s certainly a fair question. But we firmly believe that this is not just useful, but necessary. Because politicians, journalists and others whose voices shape our public conversation often seem to conflate community spaces in which we might share casual or incidental interactions with those which truly make us feel a part of something bigger than ourselves; and in which we are genuinely liable to forge connections and relationships with people who we would otherwise be unlikely to meet and mix with.

And because, as a society, we all too often seem to slip into believing that charity rather than reciprocity is the heart of community. We believe that the category of connecting institution has value because the true value of social connection is frequently overlooked or dramatically underestimated by those who hold power.

We also believe that, if the connecting institutions of the previous century – such as the church, broad-based voluntary associations and trade unions – catered at once to whole communities or sections of society, were deeply hierarchical and often sought to compel or instruct people, then the connecting institutions of the twenty-first century will be local and nimble, participatory and responsive. They will go with the grain of people’s lives and fit into complex routines which also include transcontinental Zoom calls, busy family lives and Netflix.

There is, in other words, no silver bullet solution to the challenge of disconnection. Rather, the only plausible remedy to the crisis we face is all of us; the assorted initiatives and organisations through which we are each working to foster social connection; and the wider movement of community and social bridge builders of which I believe we are a part.

That said, when a new government is in place, we at Cares will be mounting a lobbying effort to convince Prime Minister Truss or Sunak and their administration to take action to spur on the development of new connecting institutions in every corner of our country. That means:

- Shaping policy programmes and funding criteria to recognise the distinct social value generated by these initiatives;

- Providing capacity-building support and enabling civic and community leaders to apply models and approaches that have worked elsewhere in a way which will work for their place;

- And endowing community organisations and groups with the rights and powers they need to innovate effectively and to lay claim to community spaces through passing a Community Power Act.

If you’re interested in joining us in that effort, we’d love to have you on board.

Ultimately, the message I want to leave you with is this: Connection does beget connection. What starts as a ripple can build to wave. I truly believe that the seeds of systemic change can be found in the meaningful and authentic encounters across difference which the organisations represented here today create on a daily basis.